Believers

Essay by Bumsita

BELIEVERS

“GHOST HUNTING in AMERICA”

Author’s Note

What follows is the first installment in Believers, a series of patchwork essays documenting the philosophical and practical landscapes of modern belief in the supernatural. The current segment concerns ghosts and the people who investigate them. Attempts are made to draw conclusions on the nature of these phenomena with the understanding that conclusions in this area will not—cannot—ever be drawn. The term “patchwork essay” describes the use of distinct, independent bursts of writing strung together to reflect an overarching literary structure, in lieu of a singular narrative line—imagine Didion, TikTok-ified. These bursts aren’t faithful to fiction or nonfiction, as the subject itself straddles these classifications. However, I’ve outlined in the text where fiction (as I intended it) begins.

The perspective through which this essay is told is decidedly personal—which is to say, it may feel limited in broad applicability and, in many places, blatantly reflective of my career as an academic psychologist. My aim is a Gestalten final effect—that the piece’s impact is most cogent in the collective—but really, my goal with this series is simply to offer an authentic, human-to-human view of ordinary people who believe in extraordinary things.

We all believe in something.

PART I: A place at the table for the family ghost.

Probably, we will never know the caress of certainty—or anything, with so much as a scrap of authority—while living in the smoke of a country left on high heat for two hundred and fifty desperate years. For none is this as true as it is for those who seek Mailer’s “social cause and effect,” a sense of order in the psychosocial stuff of humankind. Emulate as we may mastery of our domain, the unwelcome specter of unimaginable complexity is always there to draw the curtains, just when the shape of things begins to manifest beyond our window of perception.

Decades of observation have, however, left me with a few choice impressions, of which I am dubiously certain. Chief among them is a belief that mashed potatoes and good ghost stories are equalizing forces in the cultural arsenal of the midwestern American family. As a solid potato is skinned, boiled, buttered, and crushed for our soft, pale ingestion, so too are the stone-like realities of death, violence, and mental anguish alchemized at kitchen counters to become a more palatable substance. They are the common ground of youth and elders, both going down easier than their unprocessed antecedents.

In the same manner that families have recipes, in some form or another, many families have a ghost story. Extend the definition to more broad, supernatural encounters of a quasi-religious quality—to the witnessing of miracles, divine interventions, or otherworldly premonitions—and we find nearly every family has a few stored in the back of a shared psychic closet. But being as we are in the lazy afternoon of the Darwinian revolution, and privy to every brain dropping arousing enough to have achieved digital integration, it may seem that the family ghost story has fallen out of fashion—which would be a tragedy. I am comforted by the truth that this world seldom produces an entire lineage of sober rationalists.

Ghost stories are imbued with a responsibility for the inexplicable. Even at their simplest, they poke at scientifically accepted boundaries of life and death. In their communal form—meaning cultural or regional stories, as opposed to family-based ones—they function as a means of personifying shared trauma, or negative emotional experiences. Of this, the “La Llorona” or “Woman in White” haunting archetypes are prime examples, with diverse iterations that personify the extreme lows of womanhood (e.g., death of one’s children, domestic violence, heartbreak). Family stories can reflect more specific toils—like individual struggles with change, or the pain of lacking agency in contexts of adversity. The haunted house story, for example, often occurs in instances of broader familial stress or strife, when ghostly activity seems a physical manifestation of turbulent internal landscapes.

To this end, the question of whether a ghost is made of physical or psychic material is nearly inconsequential. In either instance, they are real, in the same way that philosophical ideologies and genres of music are real—not because they are tactile structures with clear boundaries, but because they are patterns inhabiting the immaterial spaces of our minds. In this inattentive universe, we are left to construct our realities, and yarn is as good a material as any.

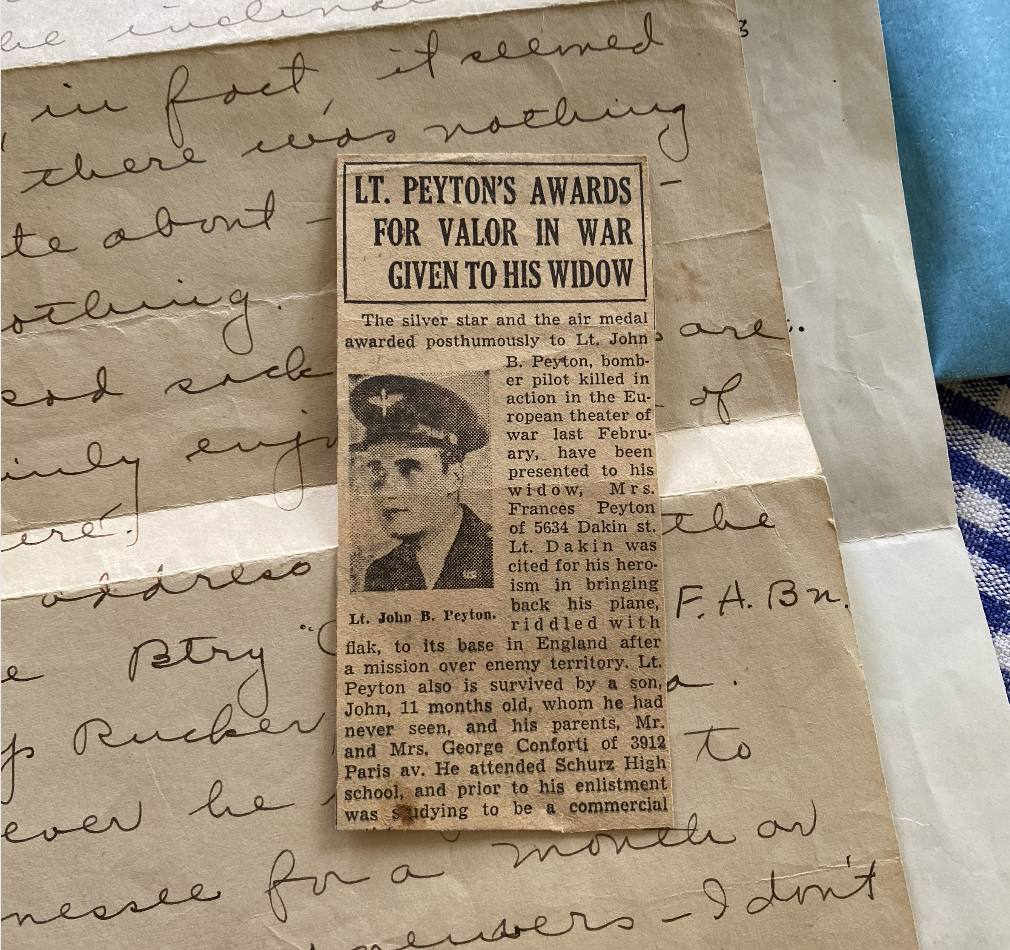

A Family Ghost Story

The letter from mother.

February of 1944. A young woman was at home with her baby girl. They lived in a modest house, consisting of equally modest rooms and furniture, on the military base where the woman’s husband was stationed. He, along with many of his friends, had enlisted in the Air Force following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Even at the fearful boiling point of World War II, he was known for his wit, and for how laughter seemed to follow wherever he went.

A letter had arrived that morning from Chicago, where the young woman’s mother lived with other family members. The young woman opened it while sitting on her bed, or perhaps at her kitchen table. It contained two cream-colored pages covered front and back in her mother’s fine handwriting.

“I received your letter several days ago, but what with one thing or another I haven’t had the inclination to write, in fact it seemed to me that there was nothing to write about—no news—no nothing.”

Her mother offered brief updates on the state of things in Chicago and assorted well wishes. In addition to having an enlisted husband, the young woman’s brother—Jack—was stationed in England as a pilot in the European theater of war. She and Jack had survived an adolescence together in the Depression-era Chicago of Al Capone and were now having their young adulthood (complete with new marriages and new babies) interrupted by global warfare. Her mother sent along Jack’s updated mailing address. The tone of the letter then shifted.

“I know you won’t laugh at this—this morning I was lying in bed, about 7:40 a.m. half asleep and half awake, and I heard Jackie say the words ‘Beneath the softly falling snow, sleep gently my beloved’. Nothing more. Needless to say, it makes me feel so uneasy; he’s been on my mind all day long.”

Within days, the family received news that at roughly the same time that his mother had heard his disembodied voice, Jack’s plane had been riddled with flak while completing a mission over German airspace. In an act of bravery that awarded him the Silver Star medal, Jack had navigated his hobbled aircraft back to England, where he made multiple attempts to safely land before ultimately running out of fuel and crashing into the earth. He was killed instantly. Upon news of Jack’s death, the contents of her mother’s letter took on a new meaning. The young woman kept the letter for the rest of her life, as a record of her brother’s ghostly poetry—of his last words to their mother.

It was February 1944. Personal tragedies soon became indistinguishable from the global. Five months after Jack’s death, the first successful test of the atomic bomb took place in the deserts of New Mexico. Twenty days later the new technology was used to instantly kill 160,000 Japanese civilians in mankind’s most destructive singular act. Following German surrender, concentration camps were discovered by ally forces, and six million became a number measured by the width and depth of ditches. Humanity burned in the wind on the long fall from grace.

And yet: life went on. The young woman’s husband survived the war and used his wit to grow a successful career in advertising. In 1949, they had another baby girl, who grew up and married her high school sweetheart. Together they moved to a farm in Kansas. They had two daughters of their own, the eldest of whom is my mother.

Jack’s widow received his honors.

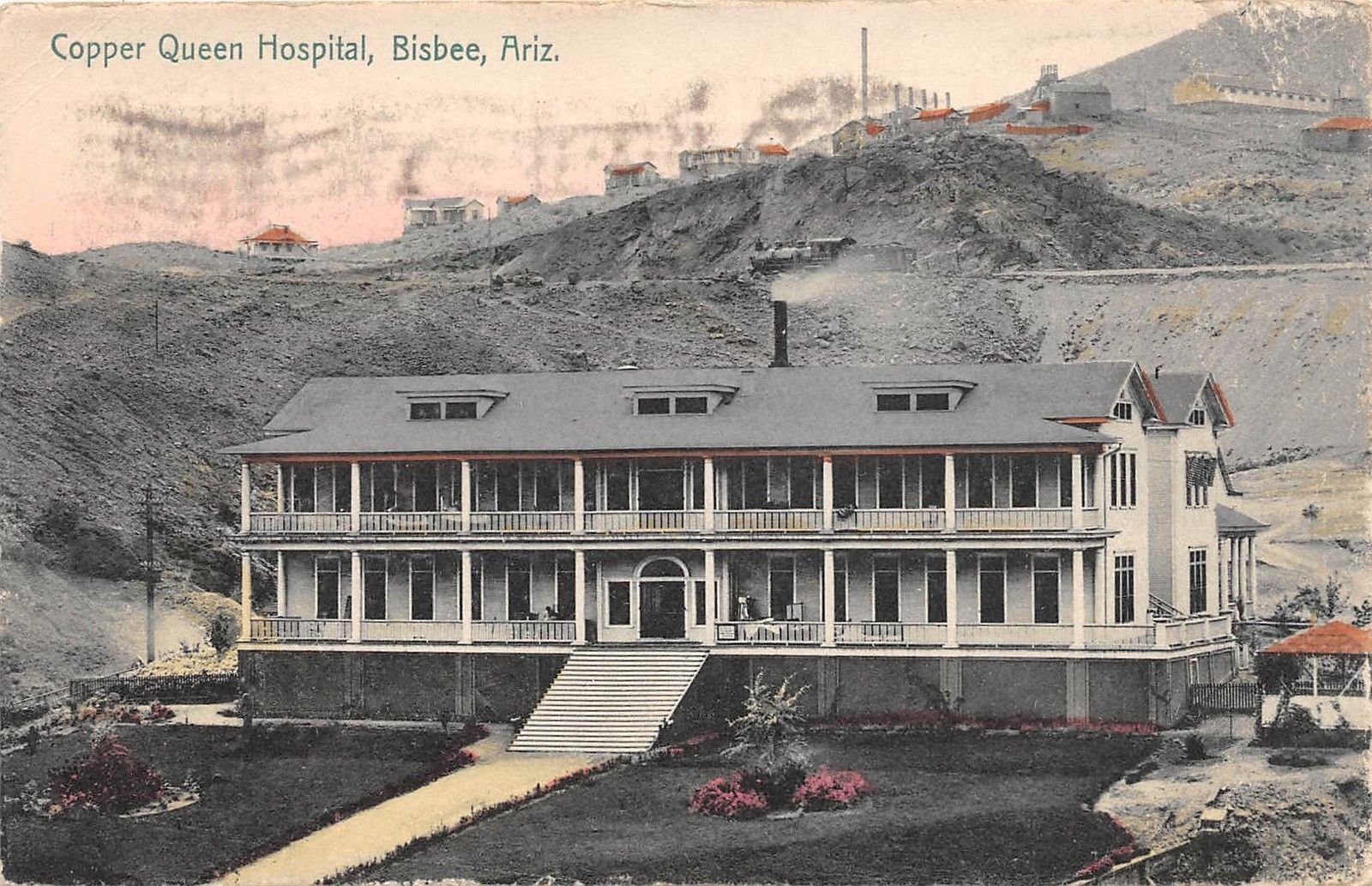

PART II: Pilots report golden-white lights at 30,000 feet in the airspace above the Bisbee Holistic Wellness Center.

In the spring of 2023, I found myself in the gymnasium of a Presbyterian church with three pairs of hands on my body. In the red earth deserts of Arizona, with the Mexican border a snake on the horizon, I had come to spend a week in solitude. The town I was in—Bisbee—was the kind of place big enough for things to happen, and small enough for flyers stapled on wooden utility poles to be an effective tool for spreading the word. I had seen an advertisement for an alternative therapy clinic offering free tarot readings and reiki on the last morning I was in town. I knew that back home in California I’d be charged for even letting these things cross my mind as thoughts. I also knew that the clinic—the Bisbee Holistic Wellness Center—was located in the town’s original hospital, dating back to the 1900’s when Bisbee was the site of a massive copper mining operation. My dual itches of frugality and novelty were scratched and, when the morning came, I made my way through Bisbee’s schizophrenic alleyways to their back door.

I signed in and was led into the small gymnasium—also part of the old hospital—that is shared by the clinic and a local church. Despite being a room full of people, the noise wasn’t above a warm murmur, and the air had the energy of a throaty exhale. Five massage tables adorned with bodies short and tall were surrounded by small teams of reiki practitioners, the youngest of which looked to have core memories of the Watergate scandal. A woman who introduced herself as Nannie Sue asked me to sit in a metal folding chair while she blessed me for the services I was about to receive.

Nannie Sue cradled my temples in the warm plains of her palms. My world did not begin swirling, shaking, or shivering. Instead, I was met by what I can only describe as the subtle effect of knowing another soul is holding yours. I was asked to open my eyes and was guided to lie on one of the massage tables. Three practitioners circled me, two female and one male, who were closer in appearance to members of my grandmother’s prayer group than the wavy hot blondes I had associated with good-vibe wellness prior to this point. I released the visual grip on my surroundings and let myself be held. They moved intuitively around my arms, my legs, my abdomen, my head—blessing each part of my body with an intention of health.

My eyes did not open until they were gently asked to do so. One of the practitioners stood near my feet, gazing at me below a puff of fine hair. She wore a plain t-shirt that covered a spacious physical form, a body I was familiar with and that reminded me of the warm Texan woman who lived down the country road from us growing up. She moved closer and took one of my hands in hers.

“The light is so strong in you today.” The words came out so softly that they felt like they manifested themselves. She began to cry. “Someone on the other side loves you, very much.” I sat up and found that I was crying, too. We held on to one another—me and this stranger—and though we talked for minutes, I remember none of what was said. Yet even if I could outline our exact exchange, it would do little to convince you of how squarely the messages landed for me. I felt something I identified as true—or at the very least, I felt something.

She did not ask me to come back for more sessions. I was not told to sign up for a workshop and unlock my true potential, nor given instructions on which books to buy, which supplements to take to dive deeper into what had happened in that gymnasium. I was thanked for stopping by and sent back into a world that—for the first time in a long time—was an ultimate mystery.

Turn of the century in Bisbee.

This experience re-energized a gusto for the supernatural that had been leaking from my ears in small quantities across two and a half decades. I was born with an orientation toward the otherworldly. I would invent ghost stories to share with any adult who would stoop to my height, and would push even the most well-adjusted of my playmates to the edge by suggesting that spirits of dead children were living in their closets. At one point when I was in middle school, I remember spending a weekend at my dad’s house making a PowerPoint presentation on Waverly Hills Sanatorium, an abandoned and notoriously haunted tuberculosis hospital. There was no academic entity requiring this of me—I simply wanted to learn more. As time marched on, my interest extended beyond ghosts to cryptids, aliens, and serial killers. I suppose you could say I haven’t strayed from these topics so much as I’ve found a way to fold them into a livelihood with high face value credibility. Today, I am an academic psychologist who gets paid to research psychopathic traits.

But always, I return to ghosts. They are the category of weird that has had the most ancient hold on my psyche, and the one I haven’t allowed myself to explore thoroughly as an adult. It came so naturally as a kid. The setting of my mid-childhood—a 1920’s farmhouse owned by my grandparents—was prime for such predilections. The house itself was not frightening, but it did have a series of crawl spaces that lent themselves to ghostly projections. My grandpa would remark that the scariest thing anyone was going to see there was him, clad in tighty whiteys, lurking through the kitchen in the wee hours of the morning. I was also raised going to my grandparent’s Evangelical church, whose members—while mellow enough to not state outright the belief in a flesh-and-blood devil—solidified my spooky fascination by meeting it with morbid seriousness.

Simultaneously, I was raised in the golden age of reality television, and bore witness to the rise of the ghost hunting program. As a brief synopsis for the uninitiated: ghost hunting television usually follows a group of paranormal investigators over the course of an evening as they explore haunted locations. They are sometimes armed with psychic mediums, or types of “high-tech” equipment that allow spirits to communicate via energetic manipulations of the physical environment. Each show has it’s schtick—the sober scientific, the easily excitable, etc.—and they all have offered me great comfort throughout my life.

I’ve joked with colleagues in science that, were the whole academic thing to fall through, I would pursue a career in ghost hunting. This is always met with a tasteful amount of pleasant laughter—the desired effect—but I can’t help but feel like I’m discounting the spooky little girl who still resides somewhere inside me. I could never seem to shake the feeling that the paranormal is a valid part of our psychology, current and historical, and subject worthy of acknowledgement.

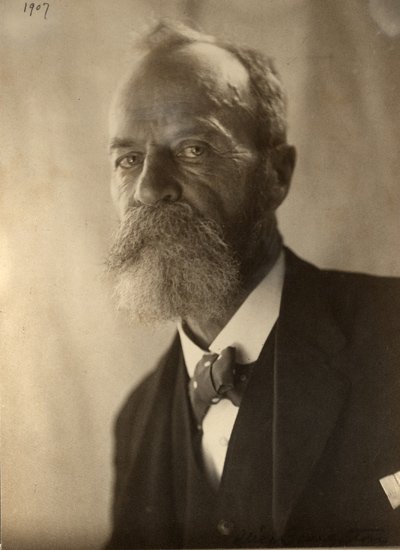

William James as a young man.

If a nut I be, then I find myself in good company. The philosopher and scientist William James (1842-1910) is credited as the “father of American psychology”, and his textbook The Principles of Psychology (published in 1890) remains perhaps the single most influential text in the history of the field. He was also a lifelong champion for scientific inquiry into the nature of supernatural phenomena which to this day remains a grave offense somewhere between career suicide and the utter destruction of credibility. He was a member (and, for two years, president) of the British Society for Psychical Research, a conglomerate of well-respected scientists interested in empirically testing claims of the paranormal. James would eventually found an American chapter of the SPR. In addition to having their own scholarly journal, founding SPR members Edward Gurney and Fred Meyers published an impeccably researched chronicle of ghostly phenomenon titled Phantasms of the Living (1886), which aimed to classify phenomena by type. Given my family ghost story, I was excited to learn that one of the most compelling categories involved visual or auditory hallucinations of a loved one occurring at or around the time of their death, when the hallucinator was not yet aware of their passing. These scientists were, for all intents and purposes, the first modern paranormal investigators.

James and his contemporaries were conducting these investigations at one of the most interesting periods in spooky history—the era of “spiritualism.” The U.S. Civil War had left Americans grappling with the realities of mass death, which led many to seek answers from mediums who claimed to have direct communication with “the spirit world.” Seances became a highly lucrative business. SPR members would investigate these supposed psychics, and more often than not, would find them to be fraudulent parlor tricksters. The rare instances where something truly inexplicable happened kept them going, though they would lament to one another that they did far more debunking than anything else. Towards the end of his life, James wrote that he would never have imagined dedicating decades to discipline without feeling any more or less sure of its makeup than when he started. When James died in 1910, it marked the beginning of the end for mainstream scientific inquiry into the paranormal.

It is from psychology's roots, then, that the ghost hunt as we know it today began. In many ways, the ghost hunt is a distinctly Anglo activity, in that it tries very hard to meet a standard of extreme rationality. Colonial attitudes towards superstition are that it is foolish, uncivilized, and a sign of inferiority. Yet superstition is the very heart of the phenomena ghost hunts are attempting to explore. As a result, the ghost hunter (who, by the way, prefers the moniker “paranormal investigator”) is an individual cursed to an eternal straddle of two worlds—too weird for mainstream rationalists, and too rational for traditional spiritualists. They have attempted to prove their worth to science-y types through the use of investigative technology—things like electromagnetic frequency (EMF) detectors, that capture subtle changes in energy fields that ghosts are purportedly able to manipulate. Though not welcomed as members of the mainstream scientific community, there are inventors and researchers who approach these topics with the same level of rigor that the botanist does their greenhouse.

For reasons I will probably never grasp, I wound up in mainstream science. I have kneeled at the altar of rationality and made my sacrifices faithfully. Yet many of the issues that plague paranormal investigators also define my work as a psychologist—the drive to quantify the inherently unquantifiable, to assign order to something as formless as the human mind. This is why now, decades away from that little girl and her ghost stories, I again feel drawn to explore these mysteries.

PART III: Investigating the investigator.

My Craigslist query.

The stranger I met on the internet asked that I call him between 11pm and 7am. In the lines of a rather cordial email, he explained that these were his working hours, and when he was generally available for discussing the paranormal. The address he was emailing from identified him as “Rick None”. Such secrecy—when paired with requests for nocturnal conversation—could make even the steeliest of eyebrows inch skyward, but this atypicality was a reflection of the oddball mission I had placed myself on. I aimed to understand a true believer—a paranormal investigator, a ghost hunter. In contexts of high strangeness, traditional definitions of red and green flags must be warped to get at the meatiest cuts—and I sensed, with a poet’s logic, that any ghost hunter worth his snuff would certainly work the graveyard shift.

Rick had responded to an ad I posted on Craigslist the week prior soliciting stories of the paranormal. Across our limited—yet pleasant—digital correspondence, Rick told me he’d had encounters with full-body apparitions and was heavily involved in the local ghost hunting scene. Out of the half-dozen or so responses I’d gotten, Rick seemed to be simultaneously the friendliest and least threatening of the bunch (indeed, one of the responses was the single, ominous sentence: “I’ve seen the devil I seen shadows following me today…no lie”). He was welcoming and forthcoming, attaching to his email fliers for community ghost hunting events he had conducted in the past. We decided to touch base on the phone. I had feigned anonymity by communicating under an alias—D.B.—and did my best to eliminate any turns of phrase which may offer inklings as to my gender, but in the pale of a slowly rising day, the jig was close to up.

The palm trees outside the glass balcony doors shuddered in an early April breeze that was equal parts wind and fog. I was alone, being put up in a San Diego hotel room by my job, which had meddled with my sense of gravity. I felt buoyant as I gathered my pre-call thoughts on a pad of hotel stationary. It was not yet 6am and things were already getting weird. I briefly considered securing my ankles to the television stand with the bedsheet, to prevent drifting too far.

Rick picked up on the first ring. I was instantly comforted by his accent—dusted with passive Mexican intonations, the trappings of an inland SoCal native—which I had heard on the voices of classmates and friends since moving to California. We volleyed a series of bumbling anecdotes, each of us trying to get an idea of whether the person on the other end was, ineloquently put, a complete crackpot. Fortunately, the Rick on the phone seemed reflective of the Rick from our email exchange—he was friendly, and open to sharing what he knew. I made a mental reminder to thank the Craigslist gods in internet stranger church that Sunday.

Like me, Rick had been interested in ghosts since childhood. I now know this to be quite common among paranormal investigators. People are either born into this interest or come to it when they see something inexplicable—extraordinary—that shakes up their worldview. Rick described how he had witnessed countless inexplicable occurrences on his investigations, with the most common being communication via EMF detector. He had also seen full ghostly apparitions, which he had a hard time describing. I got the impression that it was a very personal experience, and welcoming as he may be, there are some things you just don’t feel like talking about with strangers from the internet. But this is also common among people who witness the paranormal—something about the “high strangeness” of the phenomena makes it hard to classify in words. I was reminded of the incident two weeks prior in Bisbee, and what a hard time I’d had explaining it to others since I’d gotten home.

What struck me most about our conversation—I’m not proud to admit—was how absolutely normal Rick was. I had assumed that there would be some definitively odd x-factor, something concrete that I could use to identify the line between ME (rational scientist) and THEM (card-carrying believers in the paranormal). Instead, I found that Rick and I generally agreed on most things. We both felt that there was some element of the human spirit that remains unquantifiable, and that instead of running in opposition to science, explorations of the paranormal may hold significance for understanding humankind and our innermost systems. The only place where we seemed to diverge was in methodology. I held firm to my conviction that paranormal investigation technology is futile in reaching any meaningful consensus, and he pointed out how they’ve elevated his understanding of the supernatural.

In all, we talked for nearly forty minutes. We laughed about the hypocrisy of the religious institutions we were raised in—how we were told to pray to a Holy Ghost but were discouraged from acknowledging the existence of other kinds of ghosts. We realized that we shared a passion for criminal justice reform, and that Rick’s kids (roughly my age) were also pursuing higher ed. Before we hung up, Rick invited me to join two community Facebook pages that he uses to organize ghost hunting meetups. I thanked him for his time, and we said goodbye.

I joined the Facebook groups. About a week later, Rick posted a flyer for their next community ghost hunt. It was set to take place in late May—and I would be there.

PART IV: What we mean when we say “crazy”.

I have written elsewhere—when I was a few years younger, and still learning to screw my head on in the morning—that paranoia is America’s favorite pastime. I used this declaration to open a piece about the Satanic Panic that I published in the Skeptical Inquirer magazine in 2021. This statement was, of course, wrong—America’s actual favorite pastime is poking at poor people to check if they’re still breathing—but had it been true, then calling people crazy is America’s drug of choice.

As with any groovy controlled substance, a well-calculated dose shuttles the user into a blissed out, temporary country, sneaking some self-assuredness into the garden of earthly insecurity. Yet anything that sounds too good to be true probably is, and calling people crazy—like new socks, black tar opium, and good lovin’—comes with a bill, be it physical or socioemotional. To make matters worse, barking about someone else’s insanity is god-damned addictive, and potent enough to make a government employee pawn their pocket protector and scuttle to join the broken ranks of the Los Angeles underpass mafia. It isolates, alienates, and doesn’t appear to be going anywhere.

While this drug is neither new nor geographically confined, the cultural and technological milieu of 21st century America has proven a choice environment for its continued evolution. The vitriolic clash between scientific skepticism and religious dogmatism that defined the late 1800s remains burrowed like a botfly in our pink underbelly, telepathically selecting the key in which we play. Alongside advances in chewing gum and the domestication of fiddle leaf fig trees, a hallmark of modern America is its serious business of pathologizing. Scientists with twigs have drawn lines in the sand to tell us where sadness ends, and depression begins—and conveniently, they can sell you pills for both. This broad comfort with diagnosing works in harmony with the prehistoric joy of labelling to produce an environment where a single ill-placed belief can shoot an otherwise sane person directly to the Great Loony Bin—a place built not of brick and mortar, but of a psychosocial material stronger than iron.

While the title of “crazy” is bestowed, frequently and affectionately, upon women (broadly), it is also used to describe the pathology of belief. In my analysis of the latter, it seems that while belief can be lauded in manageable quantities, too much—or too weird—and we begin to puff our chests and dole accusations with chicken-greased digits. Simultaneously, widespread access to the internet has taken much of the legwork out of crafting our own opinion. Both the pointer and the pointed at can harvest information to support their positions without breaking a sweat. As a result, everyone is crazy—and everyone is correct.

The scientific Cosa Nostra—grown plump from centuries of competitive throne sitting—champions the outlook that believing in things that are not empirically proven is at best foolish, and at worst lunacy. It is complicated, then, to consider that on a cellular level, each of us is in a constant state of belief. Neurons—mysterious ganglia—housed in our occipital lobe make millions of calculated guesses to fill the gaps in our visual perception. Our bodies believe in these guesses and use them to navigate our environments with overwhelming success. The union of available sensory information and experience form what could be called “biological intuition”.

Belief is a prominent feature of our psychology, as well. A marker of healthy development, the milestone of “object permanence” describes when a child learns to believe that an item, when hidden from view, still exists. An infrequently drawn parallel to object permanence occurs a little further into life, in attachment theory. Anxious attachment styles are typified by a child’s inability to calm themselves once their mother is gone from view. However, the key to anxious attachment style is that these children are subsequently haunted by the mere knowledge of their mother’s absence—such that even upon reunion, they are unable to be calmed.

It comes as no surprise that this is viewed as a bad thing. When faulty belief (mother is gone, forever) is proven wrong by experience (mother has returned) and it doesn’t result in swift, sensible change…why, there must be something emotionally unwell about these kids. Yet that same judging science only vaguely understands the antecedents and consequences of attachment styles, despite a well-funded line of research. Out of respect for anyone who is still hanging in there—and hasn’t yet skipped to the next section—I will dilute the remaining diatribe to this: science knows but a little about most things, but acts like it is an unshakeable authority; it labels belief in something you can’t see as healthy in one context and maladaptive in another.

This is all but one rambling example of how the act of believing is present in each of us—how it is weaved into our biology, and perhaps as a consequence, our psychology. Moreover, it demonstrates how pathologizing belief is a flimsy business, as the real world is infinitely more complicated than the rules we use to define it. Despite all our mad slashing, we aren’t much closer to clearing the vines than we were a hundred years ago. “Crazy” is often a word used when we think we have someone figured out. It is a lazy simplification and tragic underestimation of a complex reality; it is standing in the Sistine chapel and saying you could “do that” if provided an afternoon and a box of Crayola.

Part V: Chaos is the closest we will get to a unified theory of ghosts.

William James as an old man.

Advancement in any domain is predicated on the generation of theory. Theories offer the framework for investigation, are built to be tested, and subsequently supported or rejected. From a broader perspective, theories could be seen as attempts to make the mess bearable—we know this from how scientists tend to cling to them like baby blankets on nights when the ivory tower gets chilly.

The lack of a unified theory is the primary element keeping ghosts from ever being empirically explored. It may also be why the paranormal investigator is often in a state of perpetual frustration, doomed to an eternity of data collection with no framework for analysis. William James recognized this and applied his formidable philosophical brilliance to the question. One possibility he outlined relied on the chaotic origins of the universe.

At the dawn of everything (as we know it today), there was ultimate chaos. Across time, a series of patterns in matter began to emerge, gradually becoming what are known now as the laws of physics. In a process similar to Darwin’s theory of evolution, the entire structure of the universe went from order-less to ordered. Mixed up in there somewhere was the emergence of time, as we perceive it, and a state we call “living” and a state we call “dead.” Life on earth began in the presence of these patterns and they combine to form what we view as “reality.”

This reality is largely viewed as stable and treated as though it has shed any vestiges of chaos. James thought this may not be entirely true. James wrote that paranormal phenomenon may reflect lingering pockets of chaos that exist within our reality, or that they in some way point to how “pattern” is not necessarily synonymous with “uniform.” This conceptualization is beautiful, in that it views these mysteries not as a foe, but rather, as an integral part of our existence. It is after all undeniable that humankind has been reporting paranormal phenomenon across recorded history. Carl Jung would later make the argument that each iteration of society projects onto these phenomena our time-sensitive characteristics, which alters the nature of how they appear to us. For example, the modern version of little green men from Mars is the same phenomenon that past cultures viewed as woodland sprites; the same stimulus viewed through two unique lenses. Combining these theories, it could be argued that paranormal phenomena describe how enduring universal chaos is perceived by beings alive at a specific time and place.

Lamentably, while these notions provide invaluable structure for understanding the nature of these phenomena, they don’t necessarily lend themselves towards science as-usual. Indeed, they describe events that are almost impossible to measure, with chaos and time-sensitivity as two pillars of their makeup. And yet, I am again reminded of psychology—which has branded itself as the study of the human mind—where each emotion, each facet of personality, each behavior has deeply individual underpinnings, and is extremely sensitive to the situation and time in which it is being investigated. We see this evident in current field-wide crises of replication, wherein results from foundational research are not upheld when the same exact studies are run in different samples of individuals. Many of the things we treated like “facts” of our universal psychology were in reality limited patterns in a general chaos, misrepresented in a fever to play ball with sciences like biology and physics. This may be, at least in part, what has driven many psychologists to incorporate these “hard sciences” into our methodology through the use of biomarkers (fMRI, heart rate, etc.).

This is all to say that it’s not so weird to investigate things that are both chaotic and intangible. It is unlikely, however, that the answers will lie in science as applied today. Philosophy and anthropology may lend themselves towards the subject matter, though experts in these disciplines already have a hard enough time putting bread on the table. If the paranormal remains a professional scarlet letter, we will be left to soak in generic mystery. Though this raises another question: if mystery is inherent their makeup, are these things even meant to be studied? Or is their illusive relationship with reality the very thing that gives them significance?

These are not questions on the mind of the standard paranormal investigator—which is a good thing. A philosophical diatribe from Zak Bagans would stretch the fabric of society to a shape it is unprepared for. From what I can tell, most paranormal investigators believe that our earthly human experience is defined by the exchange and flow of energies. These energies move our bodies and give us the power to manipulate our surroundings. They can also be directed by our emotional experiences, such that scenarios linked with intense emotional arousal (e.g. interpersonal violence, group ritual, death) can make a type of “energetic imprint” on the environment. This is—loosely—what ghosts are: the leftover energy of a time that is no longer now. It gets more complex from there, with some hauntings being personality-based (called “intelligent hauntings”) and others scenario-based (“residual hauntings”), but in general, spirits are thought to have the power to act via this invisible energy grid. While science typically agrees that the world operates on energy, the notion that it persists following earthly death has it summoning the waiter with a “check, please.”

Considered collectively, the most I can say is that there must be something to it. Even if all this jabber—from across centuries and cultures—is nothing more than a self-manifested psychic experience boosted by communal validation, it is meaningful. That this is even a question signifies to me humankind’s most foolish myth isn’t that the paranormal exists, but that we think it matters whether it does or doesn’t.

A philosophical diatribe from Zak Bagans would stretch the fabric of society.

Part VI: At this juncture, our narrator—in a fit of cross-eyed excitement—wished to include a section detailing how ghosts, UFOs, and cryptids are all crumbs stuck in the same psychic mustache. This, however, proved too onerous for our yellow-bellied narrator. Instead, what is offered now is a piece of fiction detailing the interpersonal fallings-out that occur in the aftermath of filming a fake Bigfoot video.

The suit was stuffed loosely in a heavy-duty garbage bag. It had not been folded, or placed there with any care at all.

The suit consisted of six interlocking components, each one thickly covered in fibers the color of muddy sand. The body piece—consisting of arms, legs, and torso—had a clumsy zipper running up the abdomen that was prone to snagging in the shaggy outer material. Two gloves, covered in hair on one side and palms of rubbery latex on the other, were punctuated by plastic claws, one per fingertip. A similar design had been employed in the creation of the boots, that offered a furry sheath extending to mid-calf. The mask—shaped like a large, hairy thimble—was the first component they had stuffed into the trash bag, it’s empty eye sockets now pressed flush against black plastic. The suit’s polyester lining had clung greedily to each molecule of sweat that it was offered, and now, heated by the sun shining through the truck’s rear window, it leaked the odor of moldy onions.

Ted and Calvin had not exchanged words since beginning the drive down the mountain. Instead, they had communicated through a series of subtle actions, in the primitive language that develops between two men who have been friends for a very long time. Calvin smoothly rolling down the passenger side window was a protest of the smell, Ted clearing mucus from his throat an agreement. They kept on like this as the pine trees began to thin, and the truck’s stereo steadily gathered signal from FM radio stations.

The idea had been born a few weeks prior, when Ted had found the suit stashed and forgotten in the crawl space of a house where he was working. Ted owned a small extermination company specializing in the eradication of pests that cause structural damage—termites and other wood-eating insects. He wasn’t sure why, but he had taken the suit with him when he left that day. When he got home, he laid it out next to him on the couch, and the two of them silently watched a 49ers game. Ted was a self-described professional bachelor and cherished how these unobserved moments of oddness doused him in a sense of personal freedom.

Calvin had been born with the loose backbone of a follower. He was also a deeply good man—his one saving grace, and the thing that had landed him his wife, Jess. It was unanimously agreed among Calvin’s family and friends that Jess was the adhesive that held his life together, and fortunately, it was a role that she enjoyed dearly. Calvin offered her a life that was comfortable and uncomplicated. He didn’t harbor the vaguely threatening hangups that she had felt in her ex-boyfriends, or that she frequently noticed in her friend’s husbands. The two had settled in one of those rare, happy marriages where what was lacking in passion was made up for by faithful stability.

Ted had pitched the idea to Calvin over beers, in the blurry timespan that crops up between Friday night and Saturday morning. The two had taken the first weekend of June to go fishing together for nearly ten years. For Christmas, Calvin had gotten a digital videotape recorder from his mother, which had been taken out of its box only twice—first to record an awkward five-second clip of his mother waving and saying “Merry Christmas,” and second, to shakily capture a family of deer making their way through the backyard. Ted proposed that for this year’s trip, in addition to tackle boxes and Deet, they pack the videotape recorder and the hairy suit from the crawl space. Calvin, unsurprisingly, leaned in the wind of Ted’s influence.

On an isolated mountainside, Calvin slipped into the main body of the suit, the inner lining abrasive against the soft skin on the back of his knees. Ted helped him put on the wobbly gloves before pulling the mask over his head. Ted looked at the face before him—wooly and expressionless, spare two brown eyes like lost children. For the rest of his life, this image would live at the edges of Ted’s sleep, and at the bottom of drained pint glasses. Ted turned and scrambled over boulders and fallen trees to where the recorder was waiting. He looked back at that man in the suit, suppressing a primal bubble of empathetic humiliation that flared in his groin. He slipped his palm beneath a hand strap made of leather and smooth black plastic, and raised the viewfinder to meet his right eye.

Slowly at first, Ted began to call out to Calvin. He told him which path to take through the pines, and how he ought to move his limbs. Calvin faithfully performed, but to Ted’s growing frustration, he looked entirely domesticated and utterly un-wild. After each take, Ted bleated a flat “again”, and Calvin felt bits of his self-worth flying off in small flames, like debris from a space capsule that is re-entering the atmosphere. Calvin tried his hardest to keep Ted’s words in his head, but could never seem to master their content.

With each direction came a growing sense that these were demands, and not requests. Calvin’s hands shook as he tripped over rocks, returning to begin the take over—and over, and over—again. He grew lightheaded and weak. The suit rubbed against his wet skin like sandpaper, and he wanted to stop, with his whole being to stop, to stop and never again walk between trees and over boulders. But for reasons that felt fully out of his control, he was powerless to the man behind the camera. The sweat that gathered in the corners of Calvin’s eyes met tears he was not conscious of, and before long his self-hatred eclipsed all other aspects of his psychology, and his body was left to carry an absent mind.

When Ted finally saw the shift, he knew that it had been worth it. Three hours of repetitive toil—of pointing and calling through trees, of being disappointed by a man in a suit—had left him with an uncontrollable frustration that was magnified with each take. Then, improbably, and just when he thought it would never happen, the creature arrived. It lumbered like a being untethered by personality, entirely made of animal instinct. Its arms swung with the mindless efficiency of a thing that doesn’t know any other way to be. He held his breath as he documented the beast’s trek across the clearing, knowing that he was capturing the impossible.

The creature stopped where Ted had told it to so many times before. Ted did not say a word. It stood heaving in silence, lit by late afternoon sunlight. Ted calmly approached, a content smile blooming across his face. He curled his fingers beneath the damp sides of the mask and raised it over Calvin’s head.

“You did great, buddy.” Ted told the man, who he then remembered was his friend.

Ted pulled the truck off the pavement and onto a dirt road that pushed deep into a forest of western sycamore. They were expected home the next morning. Though it was not uncommon for the two to pass time in silence, as the drive wore on the odor of onions became mingled with a feeling of uncertainty, and both men wondered what the other was thinking.

“What do you suppose the next step is?” Calvin’s words felt awkward in his mouth, and they called Ted back to the present moment. He applied light pressure to the gas pedal and zipped a little quicker down the dirt road.

“The way I see it,” he began, “we’ve got two options. Option one, we check to make sure the tape turned out alright. Assuming it did, we take it to one of those kiosks at the mall and get a copy made. Shouldn’t ever send out an original.” Calvin gave a stiff, reserved nod. “There’s whole societies that look for this type of footage. We send them the copy, and see what they say.”

Calvin made a wet click with his tongue on the roof of his mouth but didn’t say a word.

“Option two,” Ted continued, “we scrap the suit, scrap the tape, and don’t do anything.” He wasn’t sure where the tension was coming from, but he felt himself growing annoyed. Calvin, the spineless and obedient, was buckling, unable to handle an untruth that hadn’t even occurred yet. “Your thoughts?”

“Whatever you think is best.”

“C’mon, Calvin.” The dirt road had opened into the small clearing where they would be camping tonight. Ted pitched the steering wheel and threw the truck into park, soft clouds of dust ballooning from where the tires had settled. “It just isn’t a big deal. Just isn’t.”

The two fell back into the silence of earlier that day, only now all ambiguity had been vacuumed from the air that hung between unsaid words. They pitched their tents and got a small fire started. The sun crept far out of view, taking shelter from the tension growing between the two friends.

“Ted,” Calvin finally sighed, “I don’t know. I’m sorry, but I really don’t know.” The new image of himself, subservient and hairy and humiliated, crept in from the edges of his mind, where he had been beating it back to since Ted removed the mask. “I don’t want for people to see me like that.”

“You realize that the whole point is you’re the only one who’s going to know?” For the first time that day, the two made direct eye contact. Ted saw what he knew he would see—his uncomplicated friend, wearing the look of a loyal dog. He got the sense that he was being shamed, and for something that Calvin had allowed him to do. The weevil of regret that had squirmed in the pit of his stomach was drowned by liquid disgust.

“Don’t worry.” Ted offered a smile. “We don’t need to talk about it anymore.”

Ted went back to the truck to retrieve the trash bag and recorder. Smoothly, he opened the compartment on the side of the recorder and removed the videotape, shoving it deeply between the cushions of the back seat. He closed the compartment with a firm click, and gathered the ends of the trash bag. Calvin had his back turned and was facing the fire when Ted approached. He paused briefly before removing the suit from the trash bag dropping it into the flames.

The fire ripped through the hairs on the exterior, so fast as to live in their memories as instantaneous. A wave of intense heat caused both men to take a step back. The suit then shrunk inward, crumpling into a tarry black mass, and inky smoke began to billow up through the air of the small clearing. On top of the now formless suit, Ted tossed the video recorder. The two watched the smoldering items lose their independence and fuse as one solid lump at the fire’s heart.

They returned home the next morning, Ted pulling his truck into Calvin’s driveway. Jess stood waving behind the screen door before retreating to put on her shoes. “Promise this stays between us?” Calvin turned and asked the man seated to his left. Though his body felt that these were the last few moments of their friendship, his mind was not yet ready to accept that finality.

“Of course.” Ted looked straight ahead.

Later that week, Ted packed a copy of the tape in bubble wrap and sent it to the nation’s preeminent Sasquatch investigation society. Eight months would go by before he received a response. By that time, it had become clear to everyone in their lives that something had happened on the fishing trip. After a few half-hearted attempts to make plans, Ted stopped picking up the phone, and eventually, Calvin stopped calling. Once, about four months after the fishing trip, Jess heard Calvin sobbing in the shower. When she confronted him about it, he stared at her with bloodshot eyes and insisted he had been clearing his throat. To Jess’s best estimation, this was the first time her husband had ever lied to her face.

Ted had nearly forgotten about having sent the copy when after work one day he came home to find the red light of his answering machine blinking attractively. The man on the voicemail introduced himself as the president of the Sasquatch society, and stated that he would very much like to talk to Ted about the nature of the video he’d submitted. Ted immediately returned the call and was informed that, for the past six months, the Sasquatch society’s team of experts had been working tirelessly to de-bunk the footage, and had reached the conclusion that the quality and validity of the tape were the highest in known existence.

“I can’t stress enough the importance of this video, Ted.” The president had an unfortunate voice, that seemed to be caused by an overproduction of saliva. “This changes things—for all of us.”

With Ted’s consent, the Society released the tape to major news networks. Within a week, the unsteady footage of a Sasquatch lumbering through pine trees was beamed to living rooms across the country, and Ted was invited on a series of daytime talk shows. He was powdered and directed to sit in overstuffed armchairs, asked by large-mouthed hosts to describe what he saw. With each repetition a new detail would make itself known, and within a matter of weeks, Ted had begun to not just tell the story, but believe it.

The first time Calvin saw the footage—blasted over bottles of whiskey on the TV at the neighborhood bar—the muscles surrounding his stomach began to seize. He swiveled around on his stool and weaved his way clumsily to the toilet, where he would spend the next thirty minutes wiping stringy vomit from his nose and mouth. At home, Jess had seen the footage too, but it didn’t register as relevant until a few days later, when Ted’s all-American smile was seated next to her favorite talk show host, telling the story of how he had recorded the footage on a camping trip the previous summer.

Things had never leveled out after Calvin’s lie. Jess had done her best to write it off, reasoning with herself that a little privacy is necessary in every relationship, and that whatever had occurred on that fishing trip was something Calvin would have to share in his own time. But Calvin himself had shifted. He began to avoid her in small ways—leaving for work a little earlier, coming home a little later—but eventually, he took to genuine self-isolation.

Calvin was frustrated with himself for letting this get to him. Ted had lied about destroying the tape, yes, but he hadn’t dragged Calvin into his publicity circuit. He hadn’t pressured him into corroboration or told anyone that Calvin was involved at all. He hadn’t even asked Calvin to keep a secret. It was as though he knew, without needing to confirm, that Calvin was too obedient to ever be threatening, and this thought ate through Calvin’s bones, like a termite or other wood-eating insect.

Summers came and went. Ted’s footage had been solidified within Sasquatch lore, and Ted spent a few months a year on a convention circuit, traveling the country and speaking about his experience on panels. He eventually became known as one of the foremost Sasquatch experts in the nation. It was at one of these conventions that he met Carla, a short and wild-eyed woman who tucked the ends of her constrictive jeans into steel-toed military boots. She broke Ted apart and reassembled him in a ninety second meet-and-greet. Within the hour, she was digging through his toiletry bag for mouthwash. They were married under a harvest moon.

By the time Jess left, Calvin had drifted so far from their life together that he didn’t immediately notice her absence. The pile of dishes in the sink mysteriously grew, and one morning his underwear drawer offered him emptiness. Whatever heart he had left was broken by the fact that she had not felt moved to leave a note. He learned to live by himself, eventually, coming to rely on the freedom of mind that comes with not having to explain yourself.

In the spring of the tape’s fifteenth year, Ted found himself seated in the musty lobby of a mechanic’s shop, waiting for an oil change. He thumbed loosely through a men’s magazine and adjusted himself on the cracked plastic chair cushion. Back home, Carla was pulling down their suitcases from the crawl space, in preparation for another season on the convention circuit.

The bell attached to the front door jangled dispassionately and a stooped man with wrinkled clothes took a seat across the lobby from him. Ted did not look up from the magazine. After a few moments, though, he began to feel the uneasy quivers one gets when being stared at, and looked up to see a set of watery eyes locked on his. Fifteen years collapsed into something you could crush in your palm.

“Calvin?” The stooped man didn’t move, nor give any obvious sign of acknowledgement, though Ted knew he had heard. “Calvin.” He repeated, this time as a statement and not a question.

“How’d you do it?” The stranger with the familiar face said in a voice that was unwavering, firm. Ted had hardly seen his lips move beneath his rangy mustache and beard.

“I don’t know what you’re asking.” Ted replied. “It’s been a long time, buddy. How are you?”

“Stop.” Calvin flatly interrupted. He drew in a swift breath. “I’ve been waiting for this, I guess. I used to try to follow all the places that video took you. Never did help make any sense of it.” For the first time since they stood at that campfire, Ted felt the icy truth of what he had done, and for the first time in his life, he looked into the eyes of a man who he knew could destroy him if he wanted to.

“I never, not even once, brought you into this.” Ted tried to keep his voice even, but knew it carried the unmistakable shake of nerves.

“Cut the bullshit.” Calvin slapped his hand down on the meat of his thigh. “I may very well be the only soul alive who really knows you.” With this, he leaned towards Ted. “You’re wearing a ring now. Does she know, Ted? Does she know about what really happened? How you told me where to walk, how to swing my arms…”

“Enough.”

“Did you ever care about me, Ted?” Calvin’s voice was quieter, but just as serious. “I just wanted to forget about it, to not live with this…” he paused, thinking of what to say, “weight, this knowing I’d dance for someone who didn’t really care. You bent me out of shape and didn’t even bother to check if I was alright. You bent me out of shape and you sold me.”

“Enough, I said.” Ted had intended for this to be authoritative, but it came out with the energy of a deflated bike tire. Calvin whistled softly and sat back in his chair.

“Well, alright.” He stood up and wiped his hands on his shirt, and Ted was reminded of the grizzled prospectors from old Westerns. “I guess we’ve both got lies to tend.” He began to walk away, and Ted felt his fear eclipsed by frustration. He was brought back to those eyes in that mask, how easy they had been to disassemble. He was outraged that even now, with all that he had done, Calvin was sick with loyalty. Calvin made his way across the room, with the mindless efficiency of a thing that doesn’t know any other way to be.

“I know what I saw.” Ted spat the words at Calvin’s turned back.

“You get to believe,” Calvin opened on the door, “but I’ll always be the guy in the suit.”

PART VII: GHOST HUNTING in AMERICA.

Philadelphia, 2023

A month moved by unceremoniously, marked mainly by a set of paid bills and a steadily draining bank account. The night of the community ghost hunt had finally arrived, and in an act of grace, my husband offered to join me. He’s a good sport of the highest degree—though he remains entirely uninterested, and generally regards the paranormal with the same seriousness as he does reality television, he’s a firm believer in the power of trying new things. I was somewhat concerned that his skepticism would bolster mine and close me off to whatever there may be to witness, but was even more wary of showing up to the event solo.

The flyer identified a supermarket parking lot as the evening’s rendezvous point. In our phone call the previous month, Rick had told me how in the past the group’s investigation sites had been reported to local police, who would show up and ask people to please pack it up. To get around this, he no longer posted the exact investigation site in the flyers—though a quick search on google maps would show a large graveyard directly across the street.

We pulled up at 9:30pm on the nose and were surprised to see a ring of nearly 25 people gathered between parked cars. Outside of a few individuals wearing t-shirts that broadcasted their loyalty to a local paranormal investigation group, there were no outward clues as to the nature of this meetup. We joined the circle and began to mingle. Many sipped drinks from a nearby Starbucks, laughing with what appeared to be good friends, and in some instances, family members. While I cannot confirm this, the group appeared relatively diverse in terms of ethnic identity, though our cars and clothing identified us all as squarely working class. Folks were in good spirits, and the whole thing had the relaxed joy of people in their element.

A bald man with an affable expression approached my husband and I, who I knew instantly to be Rick. We had not seen photos of one another—our Facebook profiles being anonymous—but I am one of those people who looks exactly as their name would suggest. We shook hands and he welcomed both of us, before being called away by another of the event’s organizers. My husband and I exchanged subtle glances. We weren’t sure what to expect, but we certainly thought it would be weirder.

Just then another couple—more outgoing than us—approached the group and, without reservation, began to ask whether anyone had seen a ghost. I was overjoyed, as this offered a way of getting the information I wanted passively. I had growing scruples that I may be treating these welcoming folks as sideshow belief freaks, and while I may come across in text as boasting an outgoing investigative personality, I am in reality quite shy.

The curious couple was approached by one of the men wearing a paranormal investigation shirt—clearly, this was not his first rodeo. The man was round of belly yet wiry of limb, and had the kind of face that is hard to imagine without deep wrinkles. From below a boyish flop of box-dyed brown hair, a set of utterly serious eyes locked on to his targets. He told us that as a boy he had played in the Florida Everglades, navigating a small boat to remote places on the region’s winding rivers and inlets. He and his buddies would often camp for the night out there on shores of loose sand. One night they were awoken by the sound of distant chanting, and across the water in the distance they could see a large fire surrounded by figures in black robes. They watched in horror as a screaming young woman was lowered into the flames. When they made it back home they told everyone they knew about what they saw in the swamp—and nobody believed them. Years later, he told us with unblinking gravity, the bones of a young woman were discovered, buried in the very murky soil where he and his friends had witnessed the “black mass”. The discovery halted the construction of a golf course, and had made the news. While not necessarily a ghost story, he told the tale with such conviction that it made the specificities of the original request irrelevant.

He was interrupted by one of the organizers, who directed us to get back in our cars and make our way to the nearby cemetery. My husband and I used the few minutes away from the group to reflect on what we had seen so far. He admitted that this was different than he had envisioned—more salt of the earth than snake oil. I pretended to be less surprised than he was. We reconvened on the sidewalk perimeter of the graveyard, where the larger group began to fan out into clusters more conducive to investigation.

My husband and I followed Rick, who was joined by another first timer, Andy. Rick had brought extra EMF detectors—something he said he always does, for any first timers—and he handed one to each of us, giving a brief demonstration of how they worked before leading us to an area he knew to be highly active. Almost instantly, our detectors began to fluctuate and beep. Rick pointed into the air above us to demonstrate a lack of power lines or other obvious sources of electrical interference. Indeed, the ground below us was also hypothetically free from power lines, though I wouldn’t put it past an energy company to burrow beneath a known gravesite.

Rick began directing the ghosts to move away and towards the detectors. An approaching spirit would be signified with a beep and spike in EMF, and would indicate a response of “yes” to whatever question was being asked of them. Rick had a compassionate, curious way of addressing the spirits that was respectful and had the air of a fifth-grade teacher. It was far less dramatic than anything I had seen on TV, which lent it some power in my eyes. Rick believed these signals had meanings, and that they were intelligent, intentional responses. As a result, he talked to them in very much the same way he had talked to me.

Our group of four spent the next hour wandering around this quadrant of the cemetery, asking questions that were answered with the flashing of lights and pitchy beeping. There were a few unsettling moments, where both my husband and I agreed that whatever was picked up by the detectors felt intelligent. Notably, there was a five-minute period where the detector seemed to be responding to nearly every query, with a timing that felt distinctly conversational. It is said that there are no atheists in foxholes, and I began to understand that, similarly, it’s a lot harder to discount the paranormal while in a graveyard at midnight.

We briefly rejoined a larger group that was being led by one of the organized paranormal investigation teams. Rick, it should be noted, is not a member of any official team, preferring to explore the paranormal on his own time. This group was clearly seasoned, and investigated using other pieces of equipment, including a “spirit box”—a device that rapidly scans radio frequencies to generate white noise that ghosts can manipulate to communicate in full words and sentences. The group had picked up activity near a cluster of graves and began firing off questions—what is your name, are you happy that you’re dead, do you miss your wife, etc. Here, I thought, was the reality TV.

It was time for us to go home, and we said our goodbyes to Rick and Andy—both of whom had been incredibly pleasant across the course of the evening. We spent the drive home excitedly comparing notes. Even my husband admitted that it was, if nothing else, a damn good time.

It has been over a month. I texted Rick to thank him for being so welcoming, and asked him where I could get an EMF detector of my own. My husband and I have pulled it out a few times but haven’t gotten anything close to what was happening in that graveyard. While my opinion on the futility of ghost hunting technology hasn’t changed, I see it now as a fun way to drop in to the headspace needed for optimal enjoyment of the spooky. Following the meetup, I dove wholeheartedly into ghost hunting media, and stand firm by the statement that Rick is one of the most credible paranormal investigators I know of. His respectful, open-minded nature and willingness to share what he knows are rare in any domain, and I hope he finds the answers he seeks.

My own belief in ghosts will likely remain amorphous, driven more by philosophical definition than proof. Proof is a flimsy thing, and in all sincerity, I am not sure I want it. I am in love with mystery, and her sister possibility. But mostly, I’ve been chasing ghosts for too long to stop now.

A moldy strawberry is unceremoniously torn from its compatriots. A heaving bull circles a man in tight silk pants. A teenaged nation writes in its diary about

lovers, fools,

and other believers.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Rachel Gonzalez-Martin (University of Texas, Austin), whose conversation on the underpinnings of legends was invaluable to forming the conceptualizations expressed here. In preparation for this piece, I read Deborah Blum’s wonderful book Ghost Hunters, which outlines the incredible work (and lives) of William James and other members of the SPR. I recommend the Night Owl podcast to any readers who find this stuff interesting—they do an excellent job of chronicling the modern paranormal investigative process. For those called to the philosophical side of things, the guys at Weird Studies do an excellent podcast as well. Thanks to my parents, my grandparents, my friends, and my husband, for being kind enough to play ball with my spooky leanings. And thanks to you, reader, for the time you spent with my words.